Where Are We Now?

The shadows of Winterbourne View and Mid Staffordshire loom large over the UK healthcare system. These were not isolated incidents but symptoms of deeper systemic failures that caused profound human suffering and a betrayal of public trust (Department of Health, 2012; Francis, 2013). Years later, the critical question remains: How likely is it that such devastating scandals could happen again—and what are we doing to prevent them?

The Winterbourne View scandal, exposed in 2011, revealed horrific abuse of patients with learning disabilities at a private hospital (BBC News, 2011). Undercover filming showed residents being physically assaulted, restrained, and systematically tormented by those meant to care for them. The subsequent Serious Case Review highlighted a “culture of abuse” enabled by inadequate staffing, poor training, weak management, and regulatory failure (South Gloucestershire Safeguarding Adults Board, 2012).

Similarly, the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust scandal (2008–2009) saw hundreds of patients die needlessly due to appalling care standards, neglect, and a focus on financial targets over patient safety (Francis, 2013). The Francis Inquiry exposed a culture of fear where staff were afraid to speak out and patients’ basic needs were routinely ignored.

These events sparked widespread outrage and multiple reviews, leading to promises of reform. After Winterbourne View, the government launched the Transforming Care programme, aiming to move people with learning disabilities and/or autism out of inappropriate inpatient settings into community-based care (Department of Health, 2012). The Care Quality Commission (CQC) was granted stronger inspection powers, and there was a renewed emphasis on transparency, whistleblowing, and patient voice.

But Have These Measures Been Enough?

Recent reports suggest that while progress has been made, significant challenges remain. The National State of Patient Safety 2024 report paints a sobering picture, citing ongoing issues such as avoidable deaths, staff shortages, and pressures on an overburdened workforce (Clyde & Co, 2025; Bevan Brittan LLP, 2025). The report also highlights a “crowded landscape” of safety bodies and processes, which often appear opaque and difficult to navigate (Clyde & Co, 2025).

Disturbingly, concerns persist that another Winterbourne View-type scandal remains possible without sustained and robust action (Mencap and the Challenging Behaviour Foundation, cited in BBC News, 2012). Factors such as burnout, chronic understaffing, and workplace cultures that discourage speaking up continue to pose serious risks (HSSIB, 2025).

Recurring themes from past failures—poor leadership, inadequate training, weak oversight, and failure to listen to patients and families—remain relevant today. The Health Services Safety Investigations Body (HSSIB) continues to explore systemic issues, such as the impact of staff fatigue on patient safety, underscoring the need for greater organisational accountability (HSSIB, 2025).

Preventing Future Scandals: A Collective Responsibility

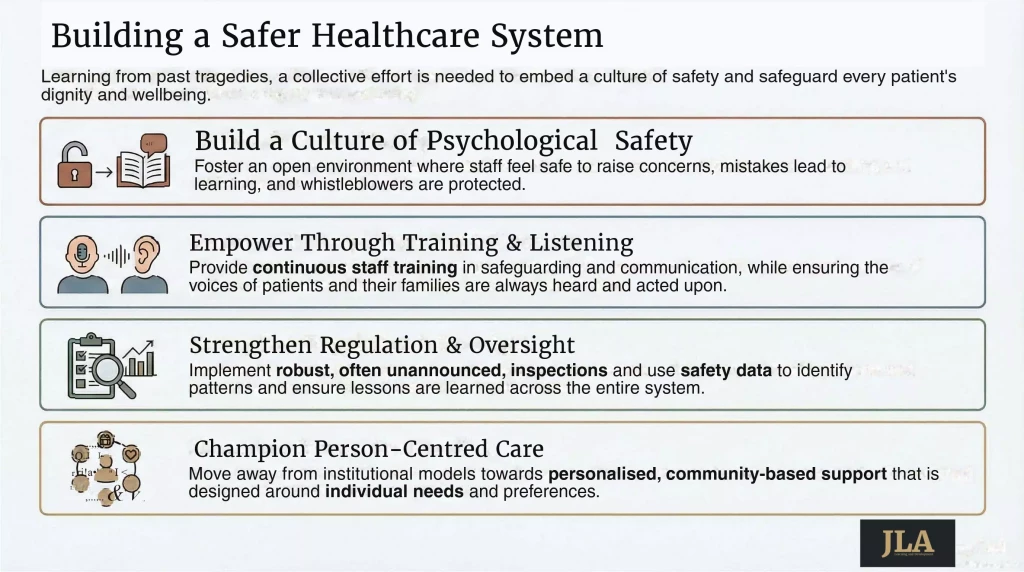

Avoiding future tragedies requires a comprehensive and sustained approach that addresses culture, systems, and individual practice. Key priorities should include:

- Embedding a Culture of Safety and Transparency: More than just policy, this means creating an environment where staff feel safe to raise concerns, where mistakes lead to learning rather than punishment, and where patient safety is the top priority. Openness with patients and families when things go wrong is essential (Francis, 2013).

- Robust Regulation and Inspection: The CQC plays a crucial role, but inspections must be consistently thorough, sometimes unannounced, and include genuine engagement with service users and families. Failures must be addressed swiftly and effectively.

- Effective Staff Training and Support: Beyond clinical skills, staff must be trained in safeguarding, communication, de-escalation, and patient rights. This is especially vital when caring for vulnerable individuals. As highlighted by organisations like JL Academy (www.jl-academy.com), continuous professional development is vital for high-quality care. Supporting staff wellbeing is equally important to prevent burnout and retain compassion in care delivery.

- Listening to Patients and Families: Often, patients and their families are the first to notice when something is wrong. Their concerns must be taken seriously, with advocacy services playing a vital role in ensuring their voices are heard.

- Strong Leadership and Accountability: Leaders must model and champion a culture of safety and integrity. There must be clear lines of accountability when care falls short of expected standards.

- Supporting Whistleblowers: Individuals who speak out about poor care must be protected and supported. Their courage is often the first defence against systemic failure.

- Focusing on Person-Centred Care: Moving away from institutional models, particularly for those with learning disabilities, toward personalised, community-based care is crucial. This means designing care around individual needs and preferences (Department of Health, 2012).

- Data Collection and System Learning: Collecting, analysing, and sharing data on patient safety incidents is critical to identifying patterns and ensuring that lessons are learned across the system (NHS England).

Conclusion

The lessons from Winterbourne View and Mid Staffordshire came at a tragic cost. Although the healthcare landscape has evolved, the risk of similar failures persists if vigilance fades. Preventing future scandals requires ongoing commitment from policymakers, regulators, healthcare leaders, staff, and the wider public.

It is not enough to say we’re going to improve things; we must actually make difficult decisions and have hard conversations about how that takes place.

JL Academy partners provides training in both positive behaviour management delivering the Timian Programme as well as delivering training on trauma informed debriefing and communication skills for professionals.

References

BBC News (2011). Winterbourne View ‘abuse’ footage released by BBC Panorama. [Online] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-20084254.”

BBC News (2012). Winterbourne View care home scandal ‘could happen again’. 7 August. [Online] Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-bristol-19154355 .

Bevan Brittan LLP (2025). National State of Patient Safety 2024: Prioritising improvement efforts in a system under stress. [Online] Available at: https://www.bevanbrittan.com/insights/articles/2025/national-state-of-patient-safety-2024-prioritising-improvement-efforts-in-a-system-under-stress/ .

Clyde & Co (2025). NHS Patient Safety 2024: Prioritising improvement efforts in a system under stress. [Online] Available at: https://www.clydeco.com/en/insights/2025/01/national-state-of-patient-safety-2024 .

Department of Health (2012). Transforming care: A national response to Winterbourne View Hospital: Department of Health Review: Final Report.

Francis, R. (2013). Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: The Stationery Office.

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (HSSIB) (2025). The impact of staff fatigue on patient safety. [Online] Available at: https://www.hssib.org.uk/patient-safety-investigations/the-impact-of-staff-fatigue-on-patient-safety/investigation-report/

JL Academy. [Online] www.jl-academy.com .

NHS England (n.d.). Safeguarding. [Online] Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/safeguarding/ .

South Gloucestershire Safeguarding Adults Board (2012). Winterbourne View Hospital: A Serious Case Review.